Brace of John Deere X9 combines gobble 170t of wheat an hour

© James Andrews

© James Andrews In its quest to build the highest-output combine harvester on the market, John Deere came up with a machine that was also the most expensive.

Commanding a heady starting list price of more than £1m, the X9 was intended to redefine how much cutting could be done in a day, and how much customers would pay for the privilege.

See also: Lancashire engineer modifies mint Claas and Deere combine fleet

To achieve its headline 100t/hour output figure, Deere moved away from the single-cylinder format of its S-series machines, in favour of two 61cm rotors fed by a wide feeder house and crop accelerator. These give some 45% more output than the flagship of the S range – the S790i – in a package that has roughly the same external dimensions.

One customer that could see the new machine’s potential was Buckminster Farms near Grantham, Lincolnshire, which placed an order for two X9 1000 models complete with 12m draper headers.

We caught up with farm manager Matthew Wallace and operator Harry Rouston to find out how they’ve been performing.

What made you choose a pair of X9s?

Matthew We were running two Claas Lexion 8700s with 12m headers and they weren’t giving sufficient output for us to keep on top of our cutting area.

Engine power was plentiful, but the threshing area wasn’t large enough or efficient enough, meaning we were often running at 60% of the available power to prevent overloading the system and pushing up the losses.

Backup from Claas Eastern was always fantastic, and the Lexions were usually cost-effective to own as the resale values were so good. However, we decided it was time to try something different.

A couple of brands brought along demonstrators for us to try, most of which had similar limitations to the Lexion, until Farol turned up with the X9.

I’ve driven most big combines over the years and I’ve never experienced a machine like it – however fast it was pushed, it dealt with the volume of crop, gave a clean sample and kept losses to a minimum.

Even when using 95% of the engine power, the internals could cope easily with the throughput. For example, in a standing 10t/ha wheat crop with a 12m draper header on the front, it was managing to run at 9kph.

A deal was done to buy two of the smaller X9 1000s for the 2022 season, but manufacturing delays meant only one arrived.

This ran alongside one of the Lexion 8700s, but because the output was so much higher, it did almost 70% of the cutting.

The second machine arrived for the start of this season, which has been a godsend as we’ve been able to keep going and cut large areas whenever there’s been a gap in the weather.

Damp conditions don’t seem to faze them and it’s mainly the drying costs that have been dictating whether we cut or not.

© James Andrews

What headers did you go for?

Matthew We opted for 12m RD40F draper headers with the HydraFlex system that allows the table to bend and hug the ground.

This doesn’t quite have the degree of contour following as the hinged HDX model, but as our land is fairly even and not particularly hilly, it didn’t seem worth the considerable extra expense.

Performance of the RD40F has been excellent in both standing and laid crops and, for the former, we operate with the table pressurised so that it’s rigid and floats above the ground. This keeps it stable when we’re pushing on at high speeds.

Then, for flat sections, the pressure can be dropped so that the table runs on skids and flexes over the contours. You need to slow your forward speed in this mode, but it helps cleanly pick the crop off the ground.

On rough going it can be a bit unstable in full flex mode, so the addition of a wheel on either end might help support it a bit better – the hinged drapers actually have two wheels on each side for this purpose.

Harry Rouston in the cab © James Andrews

What are they like to operate?

Harry Considering they’re such big, high-output machines they’re surprisingly easy to drive, even when we’re moving between blocks of ground.

Average field size on the estate is only about 10ha and, as we tend to run both machines together, moving is something we do a lot of.

Setup is also straightforward, thanks largely to the fact that the touchscreen display is so user friendly and easy to navigate.

We can just select the crop type and set a couple of parameters such as grain quality and losses, and leave the combine to get on with it.

© James Andrews

Using a series of cameras, it also monitors the cleanliness of the sample and looks out for cracked grains, before adjusting the concaves, rotor speeds, fan speed and sieves as it sees fit.

It does a good job, too, as we never really need to override the decisions it makes.

With the combine taking care of all this, I just need to concentrate on getting the crop in cleanly and pushing it on to get the maximum output.

In standing crops, I can get it to use almost all the available engine power without causing the sample quality to drop or the losses to become unacceptable.

© James Andrews

How are the cabs?

Harry It’s such a comfortable and quiet place to sit that after a full day in the seat I feel almost as fresh as I did at the start.

I’ve got Apple CarPlay, a fridge, plenty of storage space and a climate-controlled seat that even has a massaging function.

The positioning of this is good too and, combined with the fact that the intake elevator is quite long, I get a good view of the header without having to hunch forwards.

There are several other nice touches, such as an electric door latch that means you don’t have to slam it shut, and lighting that’s so good it seems like you’ve turned the sun back on.

I know it’s a very expensive combine, but it seems like John Deere has put a huge amount of thought into getting it right.

How much can you cut in a day?

Harry The estate’s relatively small field sizes limit the output, but each machine can still easily cut 40ha a day, factoring in several moves, some of which involve taking off the headers.

In a good crop of wheat, we can average 75t to 85t/hour, which is obviously less than John Deere’s advertised 100t/hour.

However, if we didn’t have to factor in turning and working around obstacles, we would be getting near that figure.

Last year we also managed to cut 100ha of beans in a day, spread over about 10 different fields.

Do you use Machine Sync?

Harry Both X9s are running Machine Sync, which allows the combine to take control of the tractor and chaser bin.

All the chaser driver has to do is drive into a virtual box, and once they’ve accepted that the combine can take over, the tractor will automatically mirror the combine’s actions.

If I speed up or slow down, it will do the same, and if I turn a corner, it will follow the same arc.

You can set a home position for it to drive at, which I set so that the spout is centred over the chaser bin.

I then use arrows on the combine screen to shunt the tractor back and forth and from side to side to get the maximum amount of grain in there.

We use one 29t Richard Western chaser to support both combines, and this ferries the grain to a fleet of 15t and 16t trailers waiting at the headland.

The reason for this is that these are the largest we can run without being overweight on the road.

Another bonus of the chaser bin is that we only have to set up one tractor with a GPS dome and Machine Sync software, which saves a considerable amount of money.

It’s a brilliant system that definitely makes the unloading operation more efficient, but it does occasionally stop working – Farol hasn’t yet worked out why.

© James Andrews

Have they been reliable?

Matthew There haven’t been any major breakdowns, but we have had a few teething problems. These include some failed bearings on the header drives, loose retractable fingers, loose bolts on the grain pans and a few electrical gremlins.

What could be improved?

Harry It’s hard to pick holes in it as it’s such a well-engineered machine. A camera at the top of the grain tank would be handy though, as it fills so quickly it can be hard to judge how far you can push your luck once the light has come on.

Although our combines have the lower-powered 639hp engine, it’s ample for most of the crops we cut, particularly as we swath most of the straw.

However, if we were doing a lot of chopping, the 700hp X9 1100 might be the better bet as it would help maintain maximum output.

© James Andrews

Would you have another?

Matthew Purely based on the performance, the X9 would be an obvious choice next time we come to upgrade.

However, the big question will be how much they have depreciated and what the cost will be to change – unfortunately, we just don’t know that yet.

Historically, that was one of the good things about Claas Lexions. We knew they would hold their value and sell well second-hand, so it made upgrades easier to justify.

Buckminster Farms’ John Deere X9 1000 specs

- Year 2022 and 2023

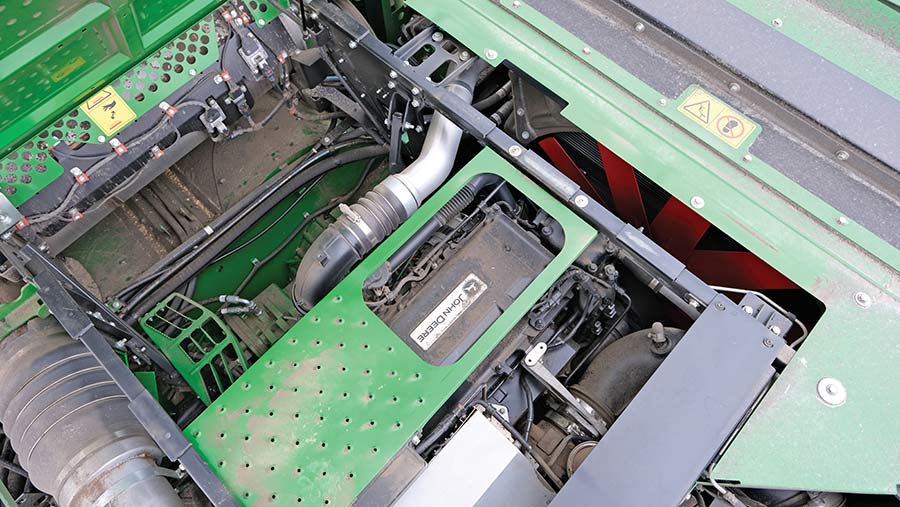

- Engine 13.6-litre John Deere six-cylinder

- Max power 639hp

- Threshing system Twin rotor with accelerator

- Rotor length/diameter 3.51m/61cm

- Header 12m RD40F draper

- Grain tank capacity 14,800 litres

- Current on-farm price £850,000 (including header)